From the August 2001 issue of 48° North

©2001 A.L. Smith

The crew of Great Escape records, “The most beautiful place we’ve ever seen.” Incognito adds, “Spectacularly beautiful.” Our Thrill declares, “God’s gift to the human race.” Entries in the guest log soon run out of superlatives to describe what awaits the traveler who journeys to Princess Louisa Inlet Marine Park on British Columbia’s south coast.

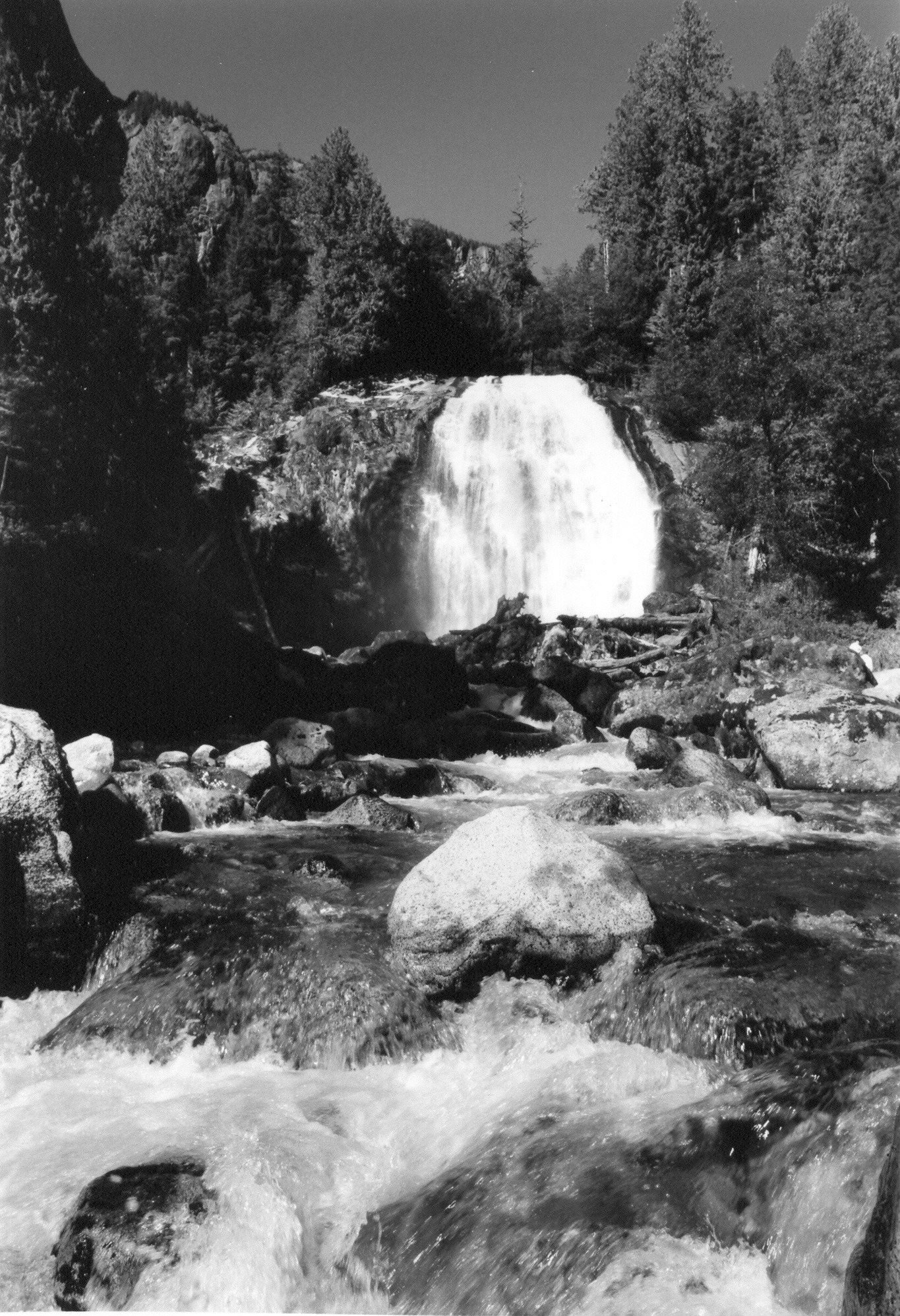

Here, near the end of the long and twisting Jervis Inlet, you find a five-mile long notch in the side of a mountain carved by titanic forces over eons of time. The water is deep and its surface is undisturbed by wind or waves thanks to a ring of steep mountains that rise several thousand feet. In the spring, melting snow form dozens of waterfalls that flow over the edge of the cliffs, plummeting down to the trees below. Many join together and flow to the head of the inlet terminating in the thundering white mass of Chatterbox Falls whose drone is a constant background noise. It creates an ideal setting that is responsible for Princess Louisa Inlet being voted “most scenic natural anchorage” in the world. Many cruisers treat themselves to repeat visits. The record must surely be held by the operator of the Egmont Water Taxi who brags in the guest log, “154th trip!” With all the common words, such as “magnificent” and “spectacular,” already overused, it is no wonder that writers find themselves “adjectively challenged” when confronted with this geological wonder of nature.

I could understand these elated observations having previously visited the world renowned anchorage in 1995. Ever since, I have longed to return. It didn’t take much to convince Bill and Fred that we should escape from the city for a week so they could see for themselves what all the fuss was about. To take us on our adventure Fred suggested we use his boat, White Swan,a Catalina 28 equipped with a strong diesel engine, beneficial for the long run up the normally windless Jervis Inlet. She also has a nice dodger and bimini setup that would shelter us from the September rains we would no doubt experience since the weather in the summer of 1999 had been less than ideal.

A Princess Louisa trip requires some careful planning by sailboaters for it lies in a remote spot more than 40 miles up Jervis Inlet. Once past the tiny community of Egmont, there are no protected anchorages – no grocery stores, no fuel docks – the crew and boat must be self-sufficient. However you can take some comfort in the fact that due to the popularity of Princess Louisa, there will be plenty of traffic in case you find yourself stranded. Don’t forget to allow for Malibu Rapids which guard the entrance to the park like a curse guards a Pharaoh’s tomb. Narrow enough to toss a stone across, there is a continual current that runs at speeds up to nine knots, except for a brief period at slack tide. You must consult the tide tables to find a day where a slack tide occurs at the same time you expect to arrive at the end of your 40-mile plus marathon. If you miscalculate, it will likely be dark before the next one. Once inside you are trapped until a day where there is slack water early enough to allow you time get back at least as far as Egmont while it is still light. Powerboats capable of higher speeds will of course have more flexibility in planning their arrival times and they will be able to take advantage of earlier tide turns.

Departure day arrives. Our plan is to make Pender Harbour before nightfall and leave for Princess Louisa early the following day to make our appointment with Malibu Rapids. We head out of Vancouver below clear skies and immediately run right into a stiff northwesterly. After a long day of beating to windward we arrive and elbow our way into the crowded anchorage at Garden Bay, another marine park inside Pender Harbour. When we finally drop anchor, it is dusk. Next morning, we are up before dawn to prepare to leave at first light. Not unexpectedly, we motor in calm conditions up Agamemnon Channel past Nelson Island toward the entrance to Jervis Inlet. All through the day we monitor knot meter, watch and chart to make sure we are on schedule.

Even the best plans can be flawed and ours was no exception. We thought we were smart to freeze our drinking water to use in the icebox which would give us a steady supply as it thawed. Unfortunately for us, White Swan‘s icebox is far too efficient and the slowly melting ice barely yields enough liquid each day to keep a cactus alive. On the second day Bill approaches me to ask where the orange juice is, to which I replied, ” I don’t know, you brought it.”

“I didn’t bring it. You were supposed to bring it.”

“No, I thought you were bringing it.”

“You mean, all we have to drink is beer?

Yes, and a limited supply at that. I immediately made a mental note to be more careful about these things in the future.

Amazingly the skies are cloudless and with no wind, the thermometer soars to record levels. Although we revel at our good fortune with the weather, Bill and I grumble about being forced to conserve beer during an Indian summer heat wave. Skipper Fred is a non-drinker and aware of our predicament. He has no doubt taken a careful inventory of his stash of pop in the lazarette. Surely he would not miss a couple of cans. But I have a recurring nightmare of being caught and put under the lash. It goes something like, “Miss…terrr Christian! Who stole my coconuts?”

As White Swan continues her winding march up Jervis Inlet, there is a steady migration of boats heading in both directions. I see everything from aluminum car-toppers out for a day trip to luxury power cruisers and even a mini cruise ship. Now how are they going to get that thing through Malibu Rapids? We take turns at the helm. Off watch I spend time under the protection of the bimini. My body wants to doze off due to the gentle motion of the boat but my eyes overrule. I can’t help but watch the awe-inspiring mountains pass-by. The further along we go, the more impressive they get.

In mid-afternoon we round the last bend and head straight for Malibu Rapids. It looks like we are on time. At the entrance we throttle back and keep to the middle of the constricted channel while the last bit of flood tide helps us around the dogleg turn. The mountains seem to close in behind as the pass widens on the other side and a wooden sign welcomes us to Princess Louisa Inlet Marine Park.

We have entered another world. The shore is steep-to. One must lean out from under the bimini to see the sky beyond the tops of the surrounding mountains. Somehow, stalwart evergreens have found a way to cling to the rock and grow on all but the most vertical parts. The water is as calm as the proverbial millpond, reflecting the trees so it seems as if White Swan is floating on a sea of green dye. Our senses are overloaded with the view until a strange sound breaks the spell and we are confronted with a horrific sight. They are helicopter logging in Princess Louisa Inlet! We curse at this invasion of our paradise. At least their style of logging is selective and the effects are not visible from the water. Proceeding down the inlet, it takes us about 45 minutes to reach the end. Suddenly, from around a corner, Chatterbox Falls emerges. I can easily imagine everyone on their boat reaching for a camera when they get to this point. Regrettably, the lens can’t capture it all in one shot.

At the dock, the friendly hands of fellow boaters take our lines. Once the boat is secure, we are free to wander ashore. A wooden walkway leads through the bush to a spot near the base of the falls. Standing there, you can feel the power of thousands of gallons of water falling 100 feet to the rocks below every second. The crushing force of impact generates a cool wind that carries the misty over-spray downstream in ghost-like clouds while the clamor of some runaway freight train assaults your eardrums. After this violent exhibition, the torrent is gradually transformed into a gentle stream before peacefully emptying into the sea. Some boats have chosen to lie here to a single anchor. The outflow of the stream keeps them pointing straight back with no worry of bumping into each other.

The next morning, while Fred goes off fishing in the dinghy, Bill and I attempt the hike up to the Trapper’s Cabin. After gaining much hard earned altitude, our bid is thwarted by the rising temperature and the fact that the old trail markers cannot compete with the new ones left by the logging surveyors. We return in defeat three hours later.

All is not lost however because I can now take some time to inspect Chatterbox Falls close-up. This was a sensible idea since the proximity of the icy mountain water provided relief from the heat of mid-day. Someone has thoughtfully installed a wooden bench at the end of the walkway in the shade of a large tree. Sitting here and looking over my shoulder toward the inlet I have to squint to make out any details for I am blinded by the light of a thousand suns. The mist from the falls has condensed on everything nearby. It is as if someone has sprinkled myriads of tiny glass balls throughout the trees and underbrush. From time to time other visitors pass by. Their reactions are always the same. After a spell I relinquish my choice seat and return to the dock by a different route along the shore eventually meeting up with Bill and Fred. They too are overwhelmed; Bill with the view and Fred with the small shark he has caught.

The tide tables tell us we must leave in the morning. If we delay any longer, the time of slack water at Malibu Rapids will be too late for us. It is another fine day when White Swan retraces her steps down the inlet and threads her way out through the pass into Jervis Inlet. Our speed on the return is excellent and we decide to bypass Egmont and go directly to Pender Harbour. We arrive in the early evening, the lingering autumn sun low in the sky. This time we elect to stay at one of the marinas so we will have easier access to shore facilities. After the ship is fed and watered it is the crew’s turn. We find a nearby pub and treat ourselves to a meal we don’t have to make ourselves. It is after sundown when dinner is finished and the walk back to the boat is made by flashlight.

We wake up to the now familiar sun shining through the ports. A luxurious shower and a leisurely breakfast get us ready for sea again. Outside Pender Harbour there is a gentle northwesterly breeze that motivates us to raise the sails and we sit back while White Swan reaches south at a relaxing pace of two and a half knots. The effort is wasted because the wind dies after a few minutes and the engine is needed again. The forecast is for more of the same so we decide to put in early and head to nearby Smuggler’s Cove. With Bill and Fred on the bow to direct us between the rocks, I steer through the tiny opening and find a spot to drop anchor. A stern line is made fast to one of the rings on shore and finally the engine is silent. Instantly, a wave of tranquility engulfs the anchorage. Fred is eager to head out and do more fishing from the dinghy so Bill and I get dropped off and spend a pleasant afternoon exploring ashore.

The next day the clouds have returned and we take this as a signal to head home. By midmorning it is a somber crew that is motoring south along the not-so-sunny Sunshine Coast. No one has much to say on this, the last leg of the trip. Our minds are still in Princess Louisa Inlet. None of us dares to question why we were chosen to have the best conditions of the sailing season coincide with our scarce opportunity to undertake such an excursion. We privately nod in agreement with the guest log comments of Whitehawk, “Been here before and we’ll probably be back.”